By James Newell

8 and 9 June in Italy saw the holding of five abrogative referenda as provided for by article 75 of the Constitution. This makes it possible to hold a popular referendum ‘to decide on the total or partial abrogation of a law or an act having force of law, when it is requested by five hundred thousand voters or five Regional Councils’. The article goes on to stipulate that a proposal ‘subjected to a referendum shall be approved if the majority of those eligible have participated in the vote and if it has received a majority of valid votes’. It was therefore significant that none of the proposals attracted the participation of more than 30.6% of the electorate (29.9% if one includes Italians resident abroad).

Italian citizens were called upon to vote for or against

- abrogation of the legislation preventing the reinstatement of workers in firms with more than 15 employees, found to have been unlawfully dismissed;

- abrogation of the legislation limiting the compensation to which workers are entitled if they are found to have been unlawfully dismissed by an enterprise with fewer than 16 employees;

- partial abrogation of the rules governing the maximum duration, and conditions for the renewal, of fixed-term contracts;

- abrogation of the legislation excluding liability of the principal contractor for accidents suffered by employees of contracting or subcontracting companies;

- abrogation of the rule requiring ten years of legal residence in Italy for non-EU adults applying for Italian citizenship, reducing the period to five years.

The four referenda concerning employment law were often presented, in public discussion, as originating with the so-called ‘Jobs Act’, introduced by the Renzi government in 2014 with the aim of boosting employment through greater labour-market flexibility. In fact, the referenda reflected public debate and a long-series of party and trade-union initiatives in the field dating back at least as far as an earlier referendum on employment protection in 2003. And indeed, while the first and the third of the 2025 referenda were aimed at abrogating provisions of the Jobs Act, the second and the fourth were inspired by the provisions of legislation dating back to 1966 and 2008. Despite this diversity, the four referenda were united by the common theme embodied in the slogan the trade union confederation, the CGIL, adopted to launch its campaign to gather the necessary 500,000 citizen signatures in support of each of the proposals on 25 April 2024. This was the slogan, ‘Per il lavoro stabile, dignitoso, tutelato e sicuro ci metto la firma’ (‘For employment that is stable, dignified, protected and safe, I’ll sign’).

The referendum on the citizenship law, meanwhile, originated with an initiative taken by Ricardo Magi, general secretary of the small opposition party, +Europa. Together with representatives of several other opposition parties and civil society associations active in promoting principles of equality and diversity, Magi began campaigning to achieve the necessary signatures at the beginning of September 2024, but his initiative too was one with a long history in public debate. This arose essentially from the fact that growing immigration from the 1980s, combined with the obstacles in the way of acquiring Italian citizenship (in particular, principles of ius sanguinis) had led to the presence of increasing numbers of second-generation migrants who were culturally Italian but without any citizenship rights, most obviously the right to vote. Several parliamentary initiatives had been taken in recent years in an attempt to address the problem, but all had failed in the face of opposition from the right. The referendum (potentially benefitting around 2.3 million people according to its promoters), seeking to abrogate parts of a 1992 law raising from five to ten years the residency requirement for eligibility to apply for citizenship, was therefore seen as an initiative that, if passed, would pressure the legislature to provide a definitive solution.

Once the necessary signatures (a combined 3,880,097 in the case of the four employment referenda; 637,487 in the case of the one on citizenship) had been deposited with and validated by the Court of Cassation, the five proposed referenda then had to clear two standard legal-administrative hurdles before they could be held. The first was Cassation’s check that the referendum question was in each case clearly formulated and that the objectives of the abrogation were legally coherent and internally consistent. In other words, Cassation was required to check that each question would allow the voter to know what they were voting on, that the provisions to be repealed were identifiable, and that repeal would not give rise to contradictory or absurd legal outcomes. This hurdle was cleared on 12 December 2024. The Constitutional Court was then required to ascertain that each proposal, if approved, would not violate the Constitution or cause serious legal consequences inconsistent with constitutional norms. This hurdle was cleared on 20 January 2025.

The opposition parties of the left (including the Partito Democratico (PD), Alleanza Verdi-Sinistra (AVS), Rifondazione Comunista, the Partito Socialista Italiano, Possibile and others) along with the CGIL called for a vote in favour of abrogation in all five cases.[1] Meanwhile, all three of the main governing parties sought to defeat the referenda by calling on voters to desert the polling stations. Consequently, the consultation’s outcome has given rise to essentially two, starkly contrasting, interpretations.

On the one hand, there is the narrative of political failure, favoured by the governing majority, according to which the inability of the referenda to reach the quorum was evidence that they were unnecessary, a waste of institutional energy, proof that the left had miscalculated and suffered a strategic defeat. From this perspective, not only did the turnout suggest that the proposals had failed to capture the public imagination, but the referendum on citizenship had fared particularly badly in that even among those who had bothered to vote, a large proportion (over a third) had revealed themselves to be opposed to the change. Citizens, from the Government’s perspective had rightly turned their backs on this and on employment-law proposals that would put firms under financial pressure and discourage hiring, especially of young people. The referenda were the latest in a long series that had failed to achieve the quorum; such an outcome had been widely foreseen, and therefore they could from this perspective, be justly portrayed as an act of desperation on the part of the opposition: a political manoeuvre designed to undermine the Government rather than a genuine exercise in democracy. ‘“The only real goal of this referendum was to bring down the Meloni government,” the party [Fratelli d’Italia, FdI] said on social media, posting a picture of the main opposition’s leaders. “In the end, it was the Italians who brought you down.”’ (Zampano, 2025). For the president of the Senate, FdI’s Ignazio La Russa, the outcome was proof that the opposition ‘campo largo’ (‘broad field’) was “definitivamente morto” (“well and truly dead”) (il Post, 2025).

On the other hand, there is a narrative of democratic mobilisation, favoured by the opposition parties of the left. According to this, the level of participation was a creditable outcome. For over 14 million citizens – around two-million more than had supported the governing parties at the general election of 2022 – had defied the ‘instructions’ of the authorities not to go to the polls. They had done so in the face of deafening silence concerning the referenda on the part of the mainstream media, including the publicly-funded broadcaster, RAI; and large (in the case of the citizenship referendum) and overwhelming majorities (in the case of the employment-law referenda) had voted in favour of abrogation. In doing so, they had demonstrated a commitment to principles of openness and inclusivity in the case of citizenship, and to those of caring and human dignity in the case of employment. And although the issues at stake had not been legally resolved, the referenda had served a purpose in ensuring that they would remain politically salient. For Maurizio Landini, CGIL general secretary, therefore,

“The fact is that a third of the country, between 14 and 15 million people, believe that the issues we raised are matters that require clear answers. This is a position of strength that everyone concerned will have to come to terms with. Our commitment is to move forward from this position and to build on it” (my translation).[2]

For PD leader, Elly Schlein, consequently, the right had “little to celebrate”.[3]

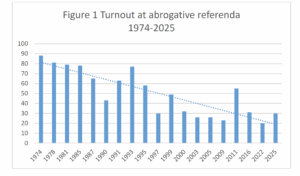

What are we to make of these two narratives? Let us begin by placing the turnout in historical perspective. Since 1970, the year in which the enabling legislation giving effect to article 75 of the Constitution was passed, there have been 77 abrogative referenda held on 19 different occasions (Figure 1). What we can see is that there has been a clear decline in turnout with the passage of time and that of the nine consultations taking place during the first twenty years, only one failed to reach the quorum whereas of the ten consultations held over the thirty years since, only one has succeeded in doing so.

Note: The figures shown are rounded averages for each set of consultations. In 2022, for example, there were five questions, each of which attracted the participation of 20.4% of the electorate. Therefore, the percentage shown is 20.

It seems likely that the increasing difficulty of reaching the quorum has had to do, at least in part, with the growing ‘technicality’ of the questions. That is, to a greater extent than in the earlier years, arguably, recent referenda have had to do with issues about how best to achieve given goals, issues requiring a certain expertise to understand them – as opposed to issues about ends and values, issues requiring ethical and ideological reasoning to resolve them. Examples would be the proposed repeal of the obligation for landowners to allow electric power lines to pass through their property of 2003 – as opposed to the 1981 referenda concerning abortion, not to mention the very first, the famous one of 1974, concerning divorce. It seems obvious that all else equal technical issues will attract lower levels of participation than issues of principle, simply because, to a much greater extent than in the latter case, they require the voter to invest in their consideration time and intellectual resources before being able to work out how to vote. Participation, in these cases is, therefore, much more costly for the voter.

However, the impact of the issues’ technical nature appears to be mediated by other variables, such as publicity and the possibility of their being presented in tandem with other issues. In 1993, for example, the relatively technical issue of the electoral system for the Senate was famously put to voters at the height of the Tangentopoli scandal; was framed by the media as a plebiscite on the existing political class in its entirety, and held centre stage in public debate for almost the entire period leading up to it. Then — as again in 1995, when Silvio Berlusconi famously urged voters not to put at risk their favourite TV programmes by supporting abrogation of legislation allowing greater amounts of advertising for programmes above a certain length – a high profile issue encouraged voters to express their views on large numbers of technical issues put to them at the same time. In 1993, in fact, voters were asked to decide on eight issues, and in 1995, on no fewer than 12. In the case of the most recent referenda, organisers hoped to benefit from a similar effect, hoping that the relatively principled question of the conditions for granting citizenship would have un effetto trainante (a ‘coattail effect’) boosting participation in the referenda on employment law. Whether it did or not, it was clearly insufficient and so lent power to the governing parties’ narrative of political failure.

Both this narrative and that of the Government’s opponents were constructed around the idea of an ideological clash between opposed electoral line-ups and this too appears to have at least some empirical support. It is likely, in other words, that those who went to vote were for the most part ideologically-driven voters of the left, as the data shown in Table 1 suggests.[4] Of course, one must be aware of the dangers of the ecological fallacy. However, it seems significant that there is a strong correlation (0.77) between the regional level turnout in the 2025 referenda, and support for parties of the left (the PD and AVS) at the most recent national election (i.e. the European Parliament elections a year earlier). Across the regions, moreover, among those who did vote, support for abrogation is more or less uniformly high (citizenship) or overwhelming (employment).

If the Government could draw heavily on the failure to achieve the quorum to construct its narrative, so too, in a different way, could the opposition parties of the left. They, not surprisingly argued that the quorum might well have been reached had the referendum not been starved of the oxygen of publicity. In support of this case, they could refer, for example, to the AGCOM communications authority’s complaint, in May, ‘against RAI state television and other broadcasters over a lack of adequate and balanced coverage’ (Zampano, 2025). They could and did also plausibly suggest that things might have been different had the governing parties not taken the – as they saw it, reprehensible — decision to encourage their supporters to boycott the referendum as opposed to participating and voting ‘no’.

In short, both the narrative of political failure and the narrative of democratic mobilisation were empirically sustainable interpretations. From a normative perspective, three considerations come to mind.

Table 1 2025 abrogative referenda: Voting by region

| Region | Turnout | PD + AVS (2024) | % yes employment | % yes citizenship |

| Valle d’Aosta | 29 | 32 | 84 | 64 |

| Piemonte | 35 | 31 | 86 | 64 |

| Liguria | 35 | 34 | 89 | 65 |

| Lombardia | 31 | 29 | 85 | 63 |

| Trentino AA | 23 | 28 | 83 | 60 |

| Friuli VG | 28 | 27 | 84 | 61 |

| Veneto | 26 | 25 | 84 | 62 |

| Emilia Romagna | 38 | 43 | 88 | 64 |

| Toscana | 39 | 39 | 89 | 67 |

| Marche | 33 | 31 | 88 | 62 |

| Umbria | 31 | 32 | 89 | 65 |

| Lazio | 32 | 31 | 90 | 69 |

| Abruzzo | 30 | 26 | 89 | 62 |

| Molise | 28 | 23 | 91 | 64 |

| Campania | 30 | 29 | 93 | 69 |

| Puglia | 29 | 37 | 91 | 66 |

| Basilicata | 31 | 28 | 90 | 64 |

| Calabria | 24 | 22 | 92 | 67 |

| Sicilia | 23 | 19 | 91 | 66 |

| Sardegna | 28 | 34 | 92 | 75 |

| Italy | 31 | 31 | 88 | 65 |

Source: our elaboration of data made available by the Ministry of the Interior.

Note: ‘PD+AVS 2024’ = combined share of the vote for the PD and AVS at the European Parliament elections of June 2024. ‘% yes employment’ = rounded average ‘yes’ vote for each of the four questions

First, it is often argued that the regular failure of referenda to reach the quorum is a sign that parties and groups have in recent years increasingly abused the Constitution’s article 75 by putting to voters technical questions more appropriately left to legislators. Whether the argument could with justice be applied to the referenda of 2025 was, at the very least, debatable. For one thing, the dividing line between ‘technical questions’ and ‘questions of principle’ is by no means clear cut. For example, the question of contractors’ liability might seem technical, but it did, arguably, involve highly significant ethical questions that ought to be matters of public debate well beyond the walls of Parliament.

To be clear, perhaps an example will be helpful: currently, if a shoe retail company were to renovate one of its stores by contracting the work to a construction firm, it would not be jointly liable for any compensation owed to a construction worker injured while using a pickaxe. This is because selling shoes is a different line of work from construction. The referendum proponents would like joint liability to apply in every case, regardless.

This would certainly encourage any contracting company to exercise greater oversight over the activities and working conditions of the subcontractor’s employees, discouraging the use of companies employing undeclared or poorly trained workers. On the other hand, it would require of the contracting companies a level of ‘expertise’ they cannot realistically possess when it comes to assessing the work of the companies to which they outsource work. And this could prove excessive and economically disadvantageous—thereby discouraging subcontracting at all (Ricardi, 2025, my translation).

Is this a technical question or a question of principle? Certainly, in light of the number of workplace accidents (around half a million) and deaths (1,077 in 2024) recorded in Italy each year (Dichiarante, 2025) it is a significant and important question.

For another thing, even relatively technical questions, when put to voters, can have important political consequences. In the case of the citizenship referendum for example, it was, arguably, highly significant that the majority in favour of abrogation was so much smaller than in the case of the other four questions. If it were true that the overwhelming majority of those who went to vote were supporters of parties of the left, then it was understandable that these parties’ representatives were worried,[5] as it suggested that discourses hostile to migrants and outsiders more commonly associated with the right had found an echo among their parties’ supporters too. Not surprisingly, League leader, Matteo Salvini, wasted little time in pouncing on the result to demand even more stringent conditions for granting citizenship than the ones already existing (il Post, 2025).

A second consideration has to do with the attempts of opponents of the proposals to achieve their ends by urging abstention and attempting to deny publicity to the referenda. Both arguably raise significant questions of democratic probity (see, for example, Casali, 2025). Urging abstention was a rational strategy from opponents’ points of view and it is, presumably, implicitly envisaged as a legitimate possibility by the fact that the Constitution’s article 75 provides for a quorum. On the other hand, one wonders how it sits with article 48, which stipulates that exercise of the right to vote ‘is a civic duty’. A constitutional lawyer would – presumably – argue that calls to abstain fall within the domain of constitutionally permitted political speech since, though described as a ‘civic duty’, voting is not a legal obligation as such. Still, one cannot help feeling that there was something slightly unsavoury about urging abstention – that a genuine democrat, confident of their position, would avoid it (seeking instead to prevail by means of participation and debate) and that advocating it could not but diminish the authority of the institutions its proponents represented.[6] For parties that like to develop discourses around themes of ‘Nation’, it was at the very least curious that they chose to take action potentially corrosive of the nation’s public institutions.

As for the relative media silence around the referenda, this too was slightly unsavoury. After all, if the members of a political community are called upon, together to take decisions of importance for the collectivity as a whole, then it is difficult to think of public events of greater weight and significance – of ones therefore more deserving of being placed at the centre of public attention.

Finally, one could not help feeling drawn, in the referenda’s immediately aftermath, to the – now longstanding (Leo, 2025) — proposal of some that a worthwhile constitutional amendment would be abolition of the quorum for abrogative referenda.[7] Yes, such a reform would in theory make it possible for passionate minorities to impose their will on less passionate or indifferent majorities. But on the other hand, it would oblige those opposed to proposals to engage in proper public debate, preventing them from being able to rely simply on procedural escamotages and public apathy in order to prevail (Pasquali, 2025). In that way, it would arguably make a significant contribution to reversing trends towards growing political indifference and declining participation.[8] No doubt a strong case could be made to the effect that the counterpart to doing away with the quorum would have to be – at the other end – the adoption of more stringent criteria groups of citizens would have to meet for the holding of referenda in the first place. Still, if abolition of the quorum did successfully raise participation, then this would conceivably perform a service of a more general kind bearing in mind that the opposite of participation – political apathy – makes it easier for public representatives to evade proper accountability, and that apathy and alienation directly assist populist leaders – whose tendency is, precisely, to demobilise citizens by claiming to be able, through the exercise of less-than-fully-accountable power, to solve citizens’ problems for them.

References

Casali, Elena (2025), ‘Stay home, stay silent: When power tells you not to vote – and democracy pays the price’, EUIdeas, 5 June, https://euideas.eui.eu/2025/06/05/stay-home-stay-silent-when-power-tells-you-not-to-vote-and-democracy-pays-the-price/

Dichiarante, Anna (2025), ‘insieme liberiamo il lavoro: Colloquio con Maurizio Landini di Anna Dichiarante’, l’Espresso,, 30 May, pp.18-21.

Dimalio, Paolo (2025), ‘Referendum, proposta di legge popolare per l’abolizione del quorum. Staderini: “In 5 ore già raccolte 5000 firme”’, il Fatto Quotidiano, 9 June, https://www .ilfattoquotidiano.it/2025/06/09/referendum-proposta-di-legge-popolare-labolizione-quorum-staderini-mille-firme/8020240/

Il Post (2025), ‘Il referendum sulla cittadinanza è andato molto peggio del previsto’, il Post, 9 June, https://www.ilpost.it/2025/06/09/referendum-risultati-definitivi/

Leo, Davide (2025), ‘Da trent’anni chi perde ai referendum chiede di cambiare le regole’, Pagella Politica, 12 June, https://pagellapolitica.it/articoli/cambiare-regole-abolire-quorum-referendum

Pasquali, Francesco (2025), ‘Il quorum è l’omicidio del referendum’, l’Opinione delle Libertà, 10 June, https://opinione.it/politica/2025/06/10/francesco-pasquali-abolizione-quorum-legittimita-referendum-partito-liberale/

Ricardi, Fracesco (2025), ‘Voto. Referendum sul lavoro: i 4 quesiti, i pro e contro, cosa c’è da sapere’, Avvenire, 2 June, https://www.avvenire.it/attualita/pagine/referendum-sul-lavoro-i-4-quesiti-i-pro-e-contro-cosa-c-e-da-sapere

Saporiti, Riccardo (2025), ‘Il referendum non ha raggiunto il quorum, non è giunta l’ora di una riforma?’, Wired, 9 June 2025, https://www.wired.it/article/referendum-quorum-non-raggiunto-abolirlo-riforma-raccolta-firme/

Zampano, Giada (2025), ‘Italy’s referendum on citizenship and job protections fails because of low turnout’, Associated Press, 9 June, https://apnews.com/article/italy-referendum-vote-citizenship-labor-law-meloni-government-opposition-d2c2b8ccfa96d27ab759cce2b4d72389

James L. Newell

University of Urbino Carlo Bo

James.Newell@uniurb.it

[1] The position of the Movimento Cinque Stelle was less clear cut in that it supported abrogation in the case of the employment law referenda while refusing to adopt an official position in the case of the citizenship referendum. Not surprisingly then, as the analysis carried out by the Istituto Cattaneo (available at https://www.cattaneo.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/2025-06-09_Referendum.pdf) suggests, in the citizenship referendum, its voters were much more divided on the issue than were supporters of the PD or AVS).

[2] Quoted by Rai News.it, ‘Referendum senza quorum, affluenza al 30,6%. Schlein:”14 milioni di voti, ci vediamo alle politiche”’, 9 June, https://www.rainews.it/maratona/2025/06/referendum-abrogativi-8-e-9-giugno-litalia-al-voto-sui-cinque-quesiti-quorum-affluenza-si-no-orari-quesiti-22b19352-c998-4dfe-9c51-1c8060236fc2.html

[3] Ibid.

[4] See, also, the above-mentioned analysis carried out by the Istituto Cattaneo (note 1), which essentially supports this interpretation.

[5] See, for example, the interview with Pierluigi Bersani during the course of the ‘Di Martedì’ broadcast on 10 June, available at https://www.la7.it/dimartedi/rivedila7/dimartedi-11-06-2025-600030

[6] Especially when the proponent in question was no less a figure than Ignazio La Russa, president of the Senate and automatic stand-in for the President of the Republic in the event that the latter is incapacitated or the office becomes vacant.

[7] As soon as it became clear that the quorum had not been achieved, the former Radical Party politician, Mario Staderini and others, launched a campaign, through the Ministry of Justice web site (https://firmereferendum .giustizia.it/referendum/open/) aimed at collecting the 50,000 signatures that would make possible, through popular initiative, the presentation to Parliament of a bill aimed at abolishing the quorum (Dimalio, 2025; Saporiti, 2025).

[8] It is worth noting, too, that the quorum can lead to perverse outcomes, depending in each case on the combination of the turnout and the proportion voting one way or the other. Most famous is the case of the referendum on electoral law reform in 1999, when 21,161,866, or 91.6% voted in favour of abrogation. This represented 42.9% of those with the right to vote, but as the turnout, at 49.6%, remained just below the threshold, the result was invalid. Yet four years earlier, in 1995, in the above-mentioned referendum on TV advertising, the 15,044, 535, or 55.7% who voted against abrogation got their way because turnout was 58.1%, even though they represented a much smaller proportion of the electorate – 31.0% – than the voters who in 1999 failed to get their way.

Condividi

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Altri Articoli

Di James L. Newell Come noto, l’8 e il 9 […]

James L. Newell (Università di Urbino Carlo Bo) A ridosso […]

James Lawrie Newell Università di Urbino Carlo Bo e co-editor […]

di Ilvo Diamanti Il voto del 25 settembre 2022, segnato dal […]

Di James L. Newell Come noto, l’8 e il 9 […]

James L. Newell (Università di Urbino Carlo Bo) A ridosso […]

James Lawrie Newell Università di Urbino Carlo Bo e co-editor […]

di Ilvo Diamanti Il voto del 25 settembre 2022, segnato dal […]

Commenti